Partnering and integration speed delivery of a hypersonic missile

Air-breathing scramjet system offers US Air Force an edge

The engineers were building a prototype hypersonic cruise missile, and they had a choice: They could either assemble it behind closed doors, then show it to U.S. Department of Defense officials, or they could do it right before their eyes.

They chose the latter.

So, at the back of an auditorium in Tucson, Arizona, a team of engineers quietly began putting together what they'd created, trying not to distract from the presentations happening onstage.

With the turn of a wrench, the integration of the many parts was underway. Section by section, the team bolted it together: the nose cone. The guidance section. The propulsion section. The controls. The fuel pump, harnessing, tubing and piping.

"When people would take a break, everyone would cluster around the back and see how things were progressing. People were paying attention to it, even though they were trying to focus their energy on the presentation material," said Nate Szyba, who led the effort for Raytheon, an RTX business.

The work was being done under an internal research and development, or IRAD, initiative called "Lay a missile on the table," also known as LAMOTT. And that's exactly what the team did – all in a day's time.

No small feat, but the real test of success was the next day, when they demonstrated the system to the same DOD leadership.

"I could sense the excitement in the room. People wanted to get up close and personal, inspect the hardware and ask questions … [there was] a lot of energy," Szyba said.

And with the flip of a switch, the team fired up the system and the launch sequence began.

"You could see the fins moving," Szyba said. "Everything was integrated that day."

That was in 2015, and there's been a lot of progress. Specifically, the missile's codevelopers, Raytheon and Northrop Grumman, successfully tested the Hypersonic Air-breathing Weapon Concept, or HAWC, for the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and U.S. Air Force in 2021 and 2022. Now the industry team is no longer in the prototype phase. Using those early lessons, they're on schedule to deliver a separate system, the Hypersonic Attack Cruise Missile, or HACM, to the Air Force. It will be the first such weapon in the U.S. arsenal.

"Developing this strategically important weapon requires bringing together the best minds and capabilities," said Szyba, who is now program director for HACM. "No one can stand alone when the mission is this important."

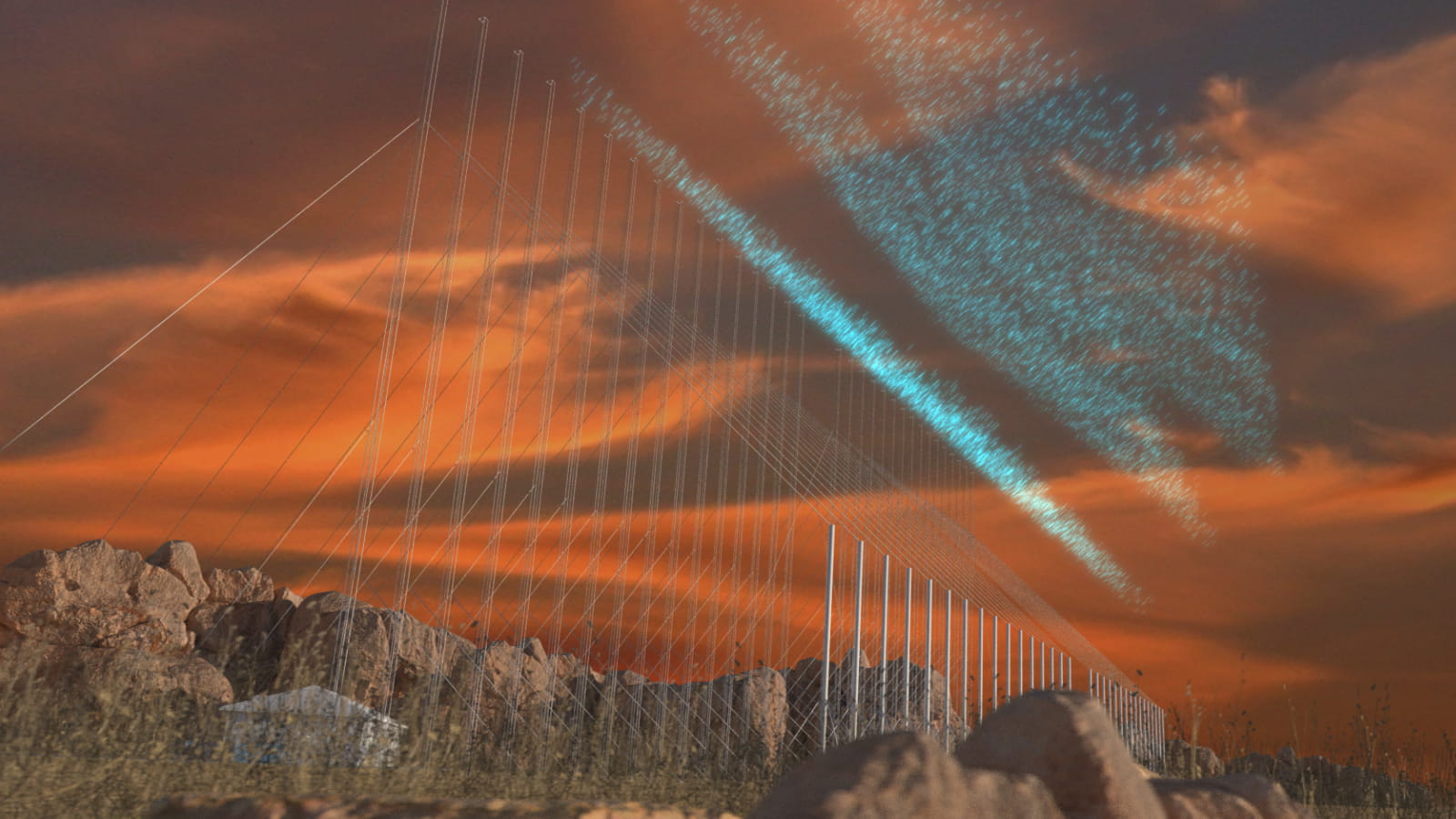

The system will serve as a major milestone for scramjet technology – a method of sustaining extremely high speeds that has been in development for decades and is about to make its real-world debut. Scramjets compress the fast-moving air around them for use as fuel.

Raytheon designed HACM, which leverages Northrop Grumman scramjet propulsion, to travel more than five times the speed of sound and cover vast distances in minutes. The Air Force has said it plans for the missile to be operational by fiscal year 2027.

"This is a tremendous responsibility that the Air Force has entrusted us with. We understand how important it is to advance our nation's hypersonic capability … a critical imperative," said John W. Otto, senior director of Advanced Hypersonic Weapons at Raytheon.

The development of hypersonic missiles has become a major emphasis in U.S. defense strategy. Hypersonic weapons' extreme speed and ability to fly at lower altitudes make them difficult to detect and track, and hard to stop. They also reduce the time it takes to perform a mission, which saves lives and protects military equipment.

The HACM contract comes after years of collaboration between RTX and Northrop Grumman on the development of hypersonic systems. That partnership started in 2013 and resulted in a 2019 teaming agreement to develop, produce and integrate Northrop Grumman’s scramjet engines and boosters onto RTX' air-breathing hypersonic weapons. The collaboration led to the development of HAWC.

The system was initially developed in the Southern Cross Integrated Flight Research Experiment, or SCIFiRE, a cooperative program with Australia to design and test hypersonic missile prototypes.

"Our scramjet technology underpins HACM and ushers in what we see is a new era of faster, more survivable and highly capable weapons," said Chris Gettinger, director in Propulsion Systems and Controls at Northrop Grumman.

Operational prototype speeds development

The Air Force's 2027 delivery date requires a relatively rapid turnaround time – but a manageable one, thanks to an early decision to develop an operational prototype versus a demonstrator.

Operational prototypes require less redesign because they're built with a specific end use in mind, whereas demonstrators mainly exist to show the core technology is feasible in general.

"It really allows us to focus on more of the affordability … and manufacturing aspects as we move forward instead of having to reinvent or redesign the wheel when it comes to our approach on a propulsion system," Gettinger said.

Integrated defense is smarter defense

Raytheon and Northrop Grumman continue to reap the benefits of those lessons learned in 2015 when Szyba and his team built that hypersonic missile prototype in an auditorium in Tucson.

Not only did their assembly approach exhibit a bit of showmanship – it even led to a helpful change in the design. As the team installed the combustor, they ended up breaking a screwdriver. So they did what engineers do: they worked around the problem and redesigned in a way that's easier to assemble.

"We're now going to leverage all the technology that we have successfully demonstrated on LAMOTT and HAWC to make a real tactical weapons system," Szyba said, "the next-generation Hypersonic Attack Cruise Missile."