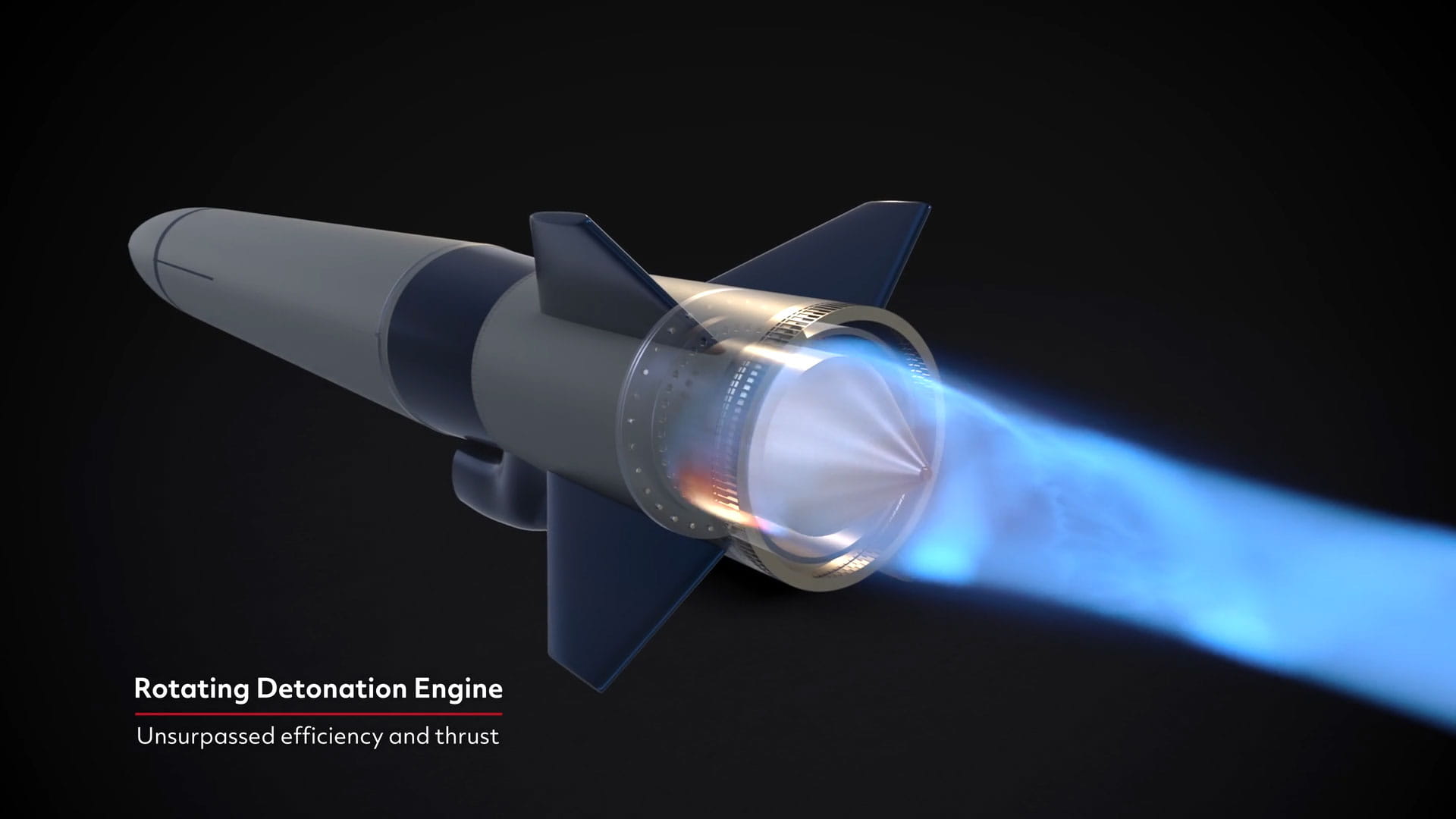

More power, no moving parts: the quest to fly a rotating detonation engine

After decades of research, tests advance innovative engine for improved military effectors

The engineers gathered at a lab in Connecticut, stood outside a testing chamber and listened.

Inside was what’s known as a rotating detonation engine – a new style of propulsion system, and one their peers, colleagues and predecessors had been researching and theorizing about for decades.

This team had built one. And it was time to find out whether it worked.

They listened for it to rumble to life, then looked at a nearby computer monitor. The sound of the vibrations and the sight of the data streaming onto the computer screen confirmed that, after much testing and iteration, the team had successfully built, at scale, an engine that had previously existed only on paper and in small prototypes.

The test marked a major victory for RTX’s work in advanced propulsion – one of several fields where experts across the company are combining highly specialized knowledge to create technology that would have been impossible otherwise.

How do rotating detonation engines work?

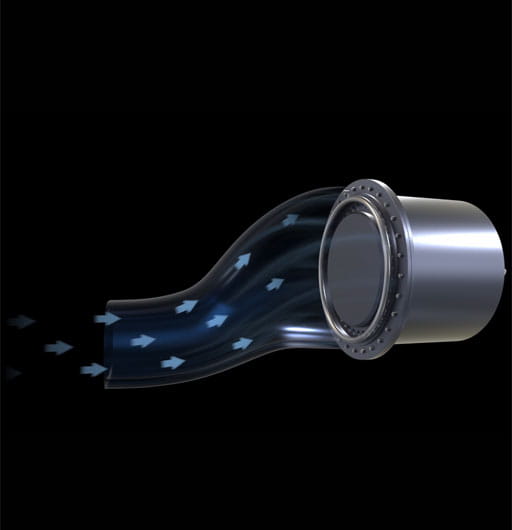

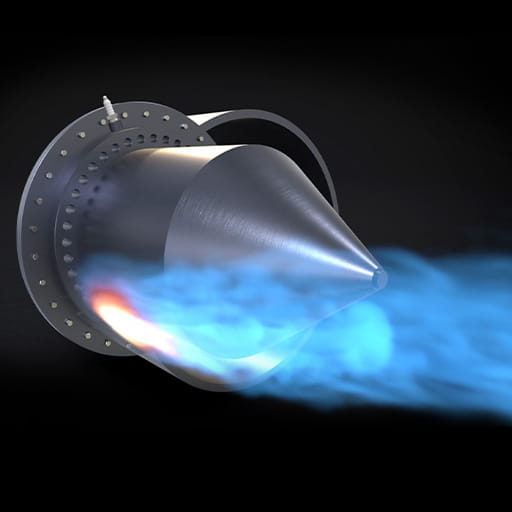

Rotating detonation engines have no moving parts and a unique design that makes them both lighter and more powerful than traditional engines. Here’s how they work.

The quest to build the engine began at the RTX Technology Research Center, which performs much of the groundwork that eventually makes its way into the company’s advanced products and systems.

There, the team used advanced modeling and specialized facilities to make the kind of progress their forerunners could only dream of back in the 1960s, when they had to rely on film to capture test data.

For example, the center has its Jet Burner Test Stand, one of the few test facilities in the United States that can reach airflow rates, temperatures and pressures that emulate high-speed flight.

“We have a facility capability that is rare throughout the country and has brought in a lot of intellectual people to pull off these types of experiments,” said Chris Greene, who has worked on RDEs at the center since 2011. “There’s momentum here to further this technology both in our facilities and people.”

After a decade of designing and testing through a series of contracts at the RTRC, Pratt & Whitney received a contract from the Air Force Research Laboratory to work with the RTRC and Raytheon to develop a rotating detonation engine for effectors. That contract led to the most recent development and performance testing.

The work demonstrated one of RTX’s key advantages in innovation: a broad portfolio of technological expertise across three businesses and the ability to collaborate among them. The RTRC did the early-stage work, then worked with Pratt & Whitney, an original engine manufacturer, to mature it into a system that could one day power a new generation of effectors such as the missiles designed and developed by Raytheon.

RTX began investigating the potential of rotating detonation engines at its RTX Technology Research Center.

Pratt & Whitney is advancing that research to produce an engine that Raytheon could fly in a weapons system.

Their work shows how RTX is uniquely positioned to solve complex challenges by bringing together experts in propulsion and defense.

“We’ve taken this technology out of the academic setting and into application,” said Chris Hugill, who leads Pratt & Whitney’s GATORWORKS development team. Support from the U.S. government, along with internal investment, will continue to be vital, he said. “Our latest test results exceeded expectations, and they make a compelling case for further investment as we move toward full system ground testing and then vehicle flight test.”

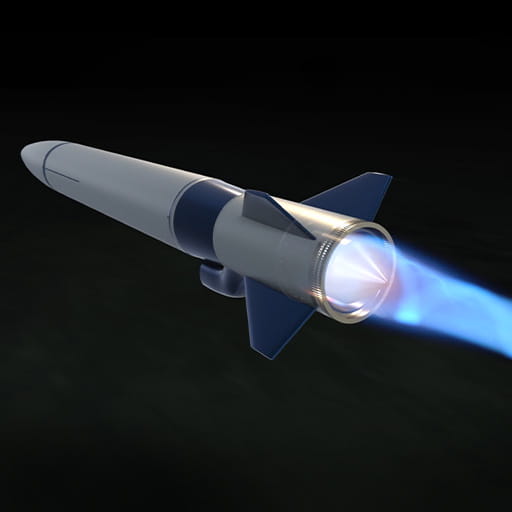

The military has much to gain from rotating detonation engines. They are highly efficient and power-dense, and their compact size creates room for additional fuel, sensors and payload. The boost in range makes it possible to engage targets at greater distances, and the simple design requires few parts and promises cost-effective production.

So, why aren’t they in production right now?

“It sounds simple, but getting the physics to work is not,” said Steven Burd, Pratt & Whitney’s chief engineer for Advanced Military Engines. “When you really try to make the design do what you want it to do consistently with the right fuels and over the right operational conditions, that’s the challenge.”

Perfecting the design

The team had to overcome two main hurdles.

First, the fuel injection had to be perfect. Generating an effective detonation wave requires the air and fuel to be mixed and introduced precisely. With too much fuel, the detonation wave may not work or be fuel efficient. With too little, it might not light – and if it did, it would not be robust enough to get the full benefit of the design.

“So, when you do not have it right, then you’re just spitting fuel into the wind,” Burd said. “It’s an art form of finding something that gives you the conditions you want repeatedly.”

The second challenge was designing and manufacturing parts for a new system.

Advanced techniques including additive manufacturing made it possible to craft durable test articles with unusual specifications, then quickly make changes. Similarly, advanced physics-based modeling guided the team’s design – and each test gave them data to feed into the model, making it smarter over time.

“You’re creating something new, which is really exciting,” Burd said. “There are so many unknowns. In this instance, it’s about bringing good engineering minds together and making the best choices.”

“You’re creating something new, which is really exciting ... it’s about bringing good engineering minds together and making the best choices.”

Preparing for flight

After roughly a year of development and performance testing, the team is focused on advancing their design and manufacturing, then integrating the engine into a ground vehicle for testing, said Beata Maynard, an associate director in Advanced Military Engines at Pratt & Whitney. She said they’re validating models with new data and plan to continue using additive manufacturing for not only test articles but engine production.

And, working with Raytheon is an efficient way to make an improved weapon.

“The government is looking for missiles that go faster and fly farther,” Maynard said. “Combining Pratt & Whitney propulsion technology with a Raytheon vehicle could result in a weapons system that addresses warfighters’ immediate needs.”

Burd said the rotating detonation engine is among the most disruptive technologies he’s worked on in his more than 25 years with the company.

“I know the team working this feels an immense sense of pride that they were able to take something that has been kind of experimented with and find a solution that we think has legs,” he said. “We’re hoping with some additional development, this will be a game changer.”