Quarterhorse is the first program on Hermeus’ roadmap to hypersonic flight and features a series of vehicles to be used for commercial testing and development efforts.

After 50 years, the F100 is going hypersonic

A proven engine finds new life in Hermeus' ambitious high-speed aircraft

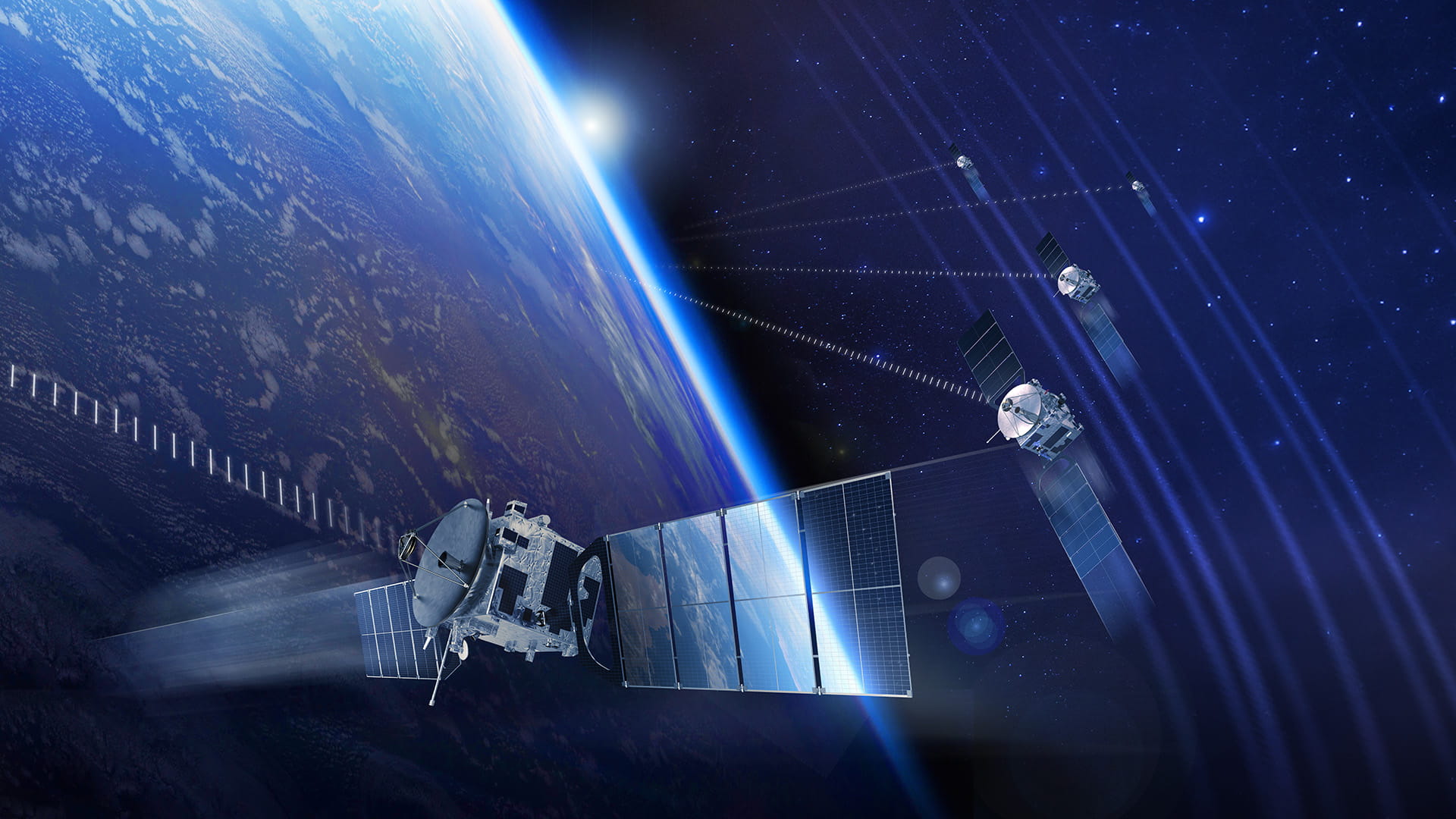

In the artist’s rendering, everything about the aircraft is new.

It’s sleek and shimmering, gliding through sun-tinted clouds. It’s moving at nearly four times the speed of sound – faster than the famous SR-71 Blackbird, which set the airspeed record some 50 years ago.

Its name is Quarterhorse, its mission is to be the world’s first high-Mach autonomous aircraft, and its creator is the U.S. startup company Hermeus.

But powering the futuristic aircraft and its ambitious goals is an engine familiar to aviation enthusiasts – the Pratt & Whitney F100.

Rather than build a new engine, Hermeus will use a modified F100, a propulsion system with 30 million flight hours and a track record aboard the F-15 Eagle and F-16 Falcon, which celebrates 50 years of flight in 2024.

Now, the engine is looking toward its next 50 years.

“Fifty years of life combined with the opportunity to remain in service for another 50 years is something that’s unique,” said Josh Goodman, senior director of the F100 program. “Pratt likes to do hard things, and utilizing the F100 in this solution gives us the opportunity to once again go solve hard problems.”

The mission

Hermeus’ long-term vision includes a hypersonic passenger aircraft that can make a 90-minute commercial flight from New York to Paris.

But first, Hermeus must prove its Chimera turbine-based combined cycle engine, which will use the F100 as its gas turbine, can achieve hypersonic speeds for Darkhorse, an uncrewed multi-mission military aircraft that would fly through contested environments at Mach 5+.

Then, it will build its third aircraft, Halcyon, a 20-passenger commercial aircraft that would make the New York-Paris flight with a yet-to-be-determined engine.

“People see it as ambitious, a little crazy,” said A.J. Piplica, Hermeus’ co-founder and CEO, “but also highly grounded in rational, realistic roadmaps to get there.”

The F100 will appear in the third prototype of Quarterhorse in 2025, where it will help the vehicle surpass Mach 2.5. Then, in the fourth prototype, it will help solve an especially hard problem called mode transition, which is when the propulsion system switches from turbo to ramjet during flight.

Here’s how they’ll do it.

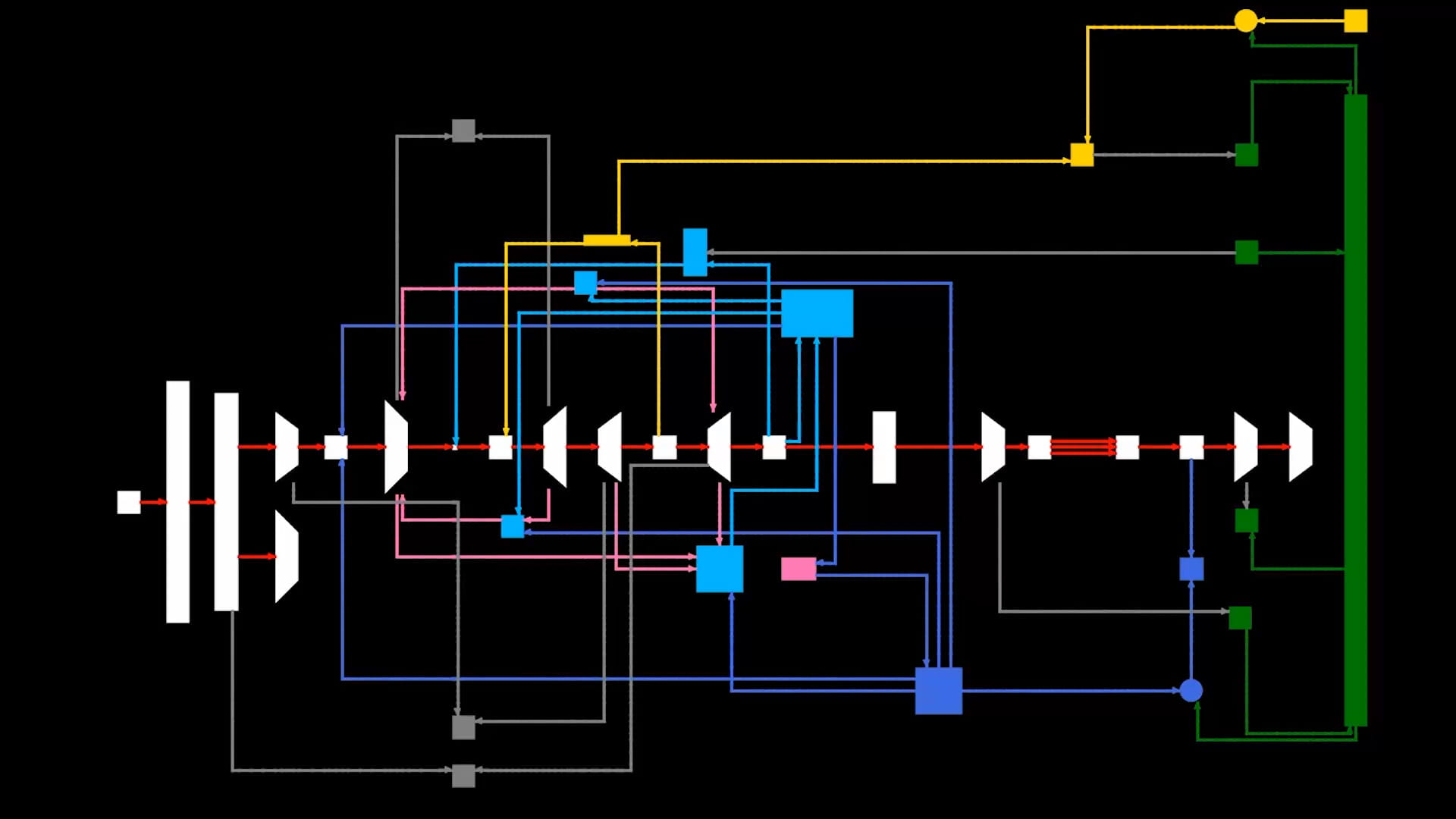

The Chimera engine works a little like a car’s manual transmission system, but rather than changing gears to go faster, the engine changes propulsion systems.

For speeds up to about Mach 2, the Chimera engine will use a turbine propulsion system, where an engine creates thrust by taking in air, compressing it and igniting it. For anything faster, it switches to its ramjet system, which needs no compressor because the air around it is already moving so fast.

Something called a precooler – a clever way of getting more performance out of the turbine engine – will help the two systems work together. By lowering the temperature of the air it takes in, the precooler gives the turbine more headroom to work harder and get the aircraft up to higher speeds.

Hermeus has already completed two major milestones by proving mode transition and precooler technologies in separate lab-based tests.

“By making a full-range, air-breathing hypersonic engine, Hermeus is setting the stage for aircraft that are capable of taking off from a regular runway and accelerating up to hypersonic speeds,” said Glenn Case, Hermeus co-founder and chief technologist. “No rockets or motherships required.”

Why the F100?

Hermeus chose the F100 for several reasons, said Mark Von Nieda, Pratt & Whitney’s F100 program chief engineer. They include:

“When you don’t have to worry about the performance of the engine, that’s huge,” Piplica said. “And then, once you’re in production, to have the maintenance, repair and overhaul infrastructure already in place both domestically and abroad, it really starts to bite down on risk on the logistics side. People ask very early in the program, ’How are you going to maintain this engine?’ Well, there’s F100 MRO shops in key places around the world already. That makes it very attractive from a product perspective.”

The F100 is also the perfect size for Hermeus’ aircraft. Smaller engines wouldn’t provide enough thrust while a larger engine would be too heavy and require more fuel.

“So, there’s a sweet spot in the design and the size, weight and thrust class of this engine that fits very well,” Von Nieda said. “It’s in the sweet spot where success is a possibility.”

The F100’s next 50 years

Von Nieda, who has worked with the F100 throughout his 40-year Pratt & Whitney career, said the engine is just as relevant today as it was when he started.

Pratt & Whitney F100-powered F-15s and F-16s are undefeated in air-to-air combat, and across the 23 countries that fly F100-powered aircraft, the engine has flown nearly three times as many hours as other fourth-generation fighter engines.

It was the first military engine to have a digital electronic engine control, which was added in the 1980s. The upgrade gave the F-16 unprecedented control and maneuverability and helped earn the F100 its nickname, “the pilot’s engine.”

“Through its evolution, this engine has become completely un-placarded. It’s all weather, any altitude and Mach number in the envelope because there are no throttle restrictions. Pilots can put it wherever they want,” Von Nieda said. “There’s a reason why Thunderbirds use F100s in their F-16s – they know that the response to their inputs is so predictable from a throttling perspective. With their hand on the stick, they know what they’re going to get out. That’s why it makes them comfortable flying just a couple inches from wingtip to wingtip.”

Of the more than 7,000 F100s produced, over 3,300 are still in service today as the company continues to add capabilities. According to Von Nieda, it’s a turn-of-the-century engine rather than a 1970’s engine, and partnerships like Hermeus’ prove there’s still room for it to grow.

“That’s why I’ve stayed in engineering pretty much my entire career – because physics is hard,” Von Nieda said. “It’s fun to push the edge of what’s physically possible. Hermeus is doing that, and it’s really cool to be involved.”