A tanning bed for hypersonic missiles

Quartz lamps help simulate heat generated from Mach 5 flight

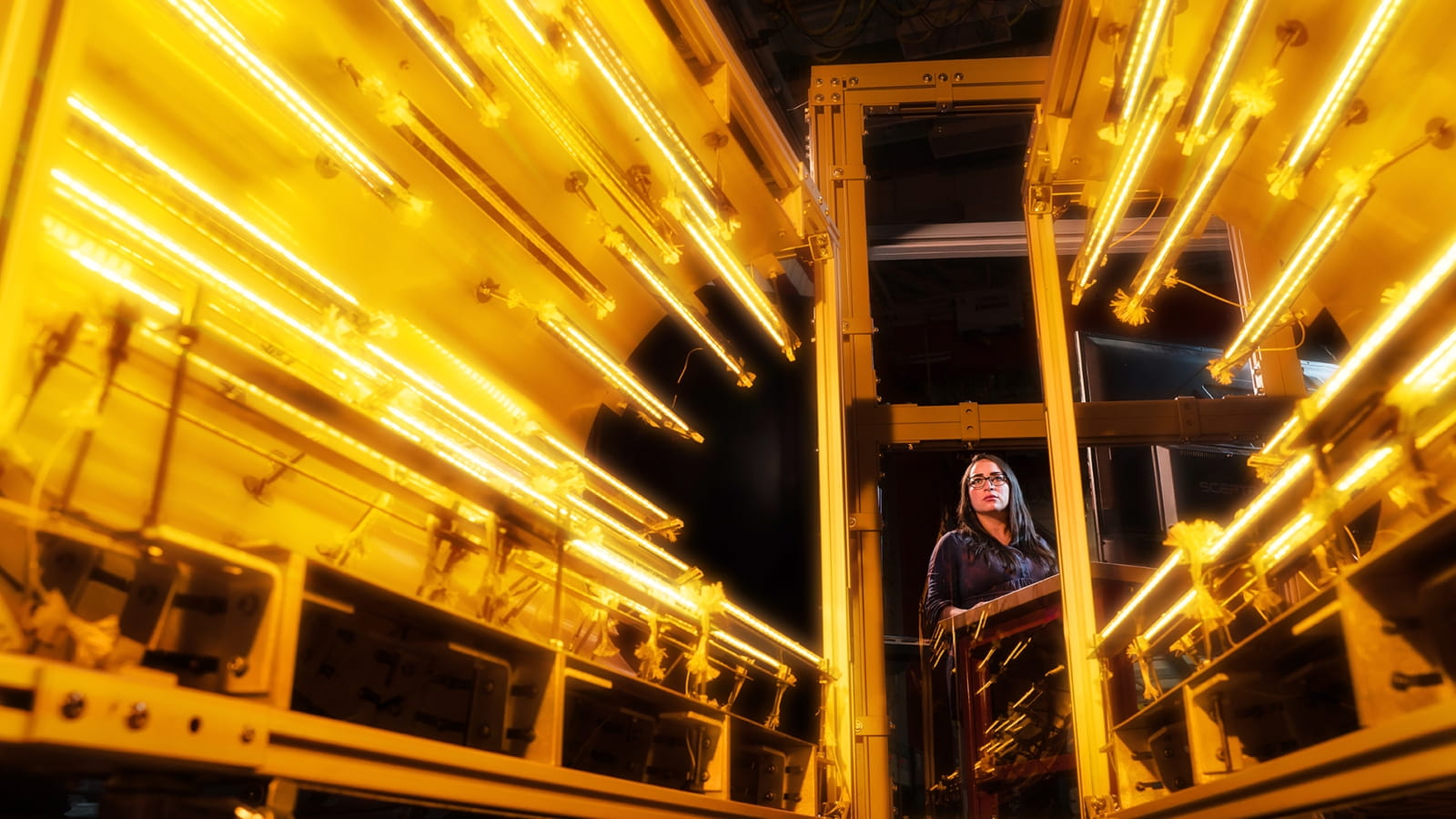

They call it the “tanning bed.”

The array of quartz lamps, built to simulate the thermal stress of hypersonic flight, can crank out temperatures in excess of 2500 degrees Fahrenheit. Raytheon, a Raytheon Technologies business, uses it in tandem with digital engineering methods such as modeling and simulation, as well as wind-tunnel testing, to evaluate and improve the performance of hypersonic airframes – those that fly faster than Mach 5 – without time and expense of actually taking them to a physical test range.

“You can park a missile in it, or a section of a missile,” said Adam Wood, an engineering fellow.

Heat is one of the key problems engineers have to overcome in designing hypersonic airframes.

When missiles travel that fast, they push large volumes of air out of the way. That creates friction – so much heat, in fact, that it would cause many common materials such as aluminum to disintegrate, said Ralph Klestadt, a chief engineer for hypersonics.

Apart from that, Klestadt said, even if an airframe stays intact, the heat can distort its shape and affect its maneuverability.

“As a system starts to heat up, parts of it will be really hot while others aren’t quite yet, causing pieces of the vehicle to grow at different rates,” Wood said. “The shape begins to change and that affects how it flies through the air. It becomes a structural issue.”

There are a number of ways to overcome the heat problem – design elements, novel materials, special coatings and so on – but no matter the method, engineers have to make sure it’s going to work. That’s where the “tanning bed” comes in.

Raytheon engineers examine a missile being tested in the tanning bed.

Flexible framework

The system consists of two half-cylinders that form a dome-like structure when put together. The bed can be expanded or reduced to fit around any particular airframe, and it can be split up and used to test multiple pieces of hardware in different locations.

The quartz lamps also have dimming switches, meaning test operators can adjust the heat level on the fly.

“We’re able to simulate the heating environment throughout a flight dynamically – as it’s happening. Heating fluctuates in flight,” Wood said.

That’s not possible in a wind tunnel, which is traditionally used to test the response of a structure and its parts to aerodynamic force. But wind-tunnel testing still has its place, Wood said – and in fact, it’s right alongside “tanning bed” testing.

“Wind tunnels allows us to test certain things we can’t test in the tanning beds,” Wood said. “We really need both to get the full understanding of what’s happening with a vehicle.”

Strategic investment

The defense and aerospace industry has used quartz lamps to heat-test systems for some time, and agencies including NASA have facilities dedicated to the approach. But the demand to use them is high – so Raytheon built its own.

“We reduce cost by working within existing Raytheon facilities,” Wood said. “And, it allows us to get our testing done faster than before.”

Plus, actual flight testing can get expensive, especially given that it offers relatively little data for the investment.

“Due to a vehicle’s space and volume constraints, we’re limited with the amount of information it provides, such as temperature, shock, vibration and pressure measurements,” Wood said. “We can collect a lot more data on the ground than we can in flight.”

As a result, ground testing continues to grow and mature together with the company’s hypersonic development efforts.

“Being able to test a hypersonic system to near flight-level heating just down the road in a lab is pretty impressive,” Wood said. “But we’re not stopping here.”